Public History in Action: Desegregation Within the Philadelphia School System

- Feb 2

- 4 min read

Updated: Feb 5

By Daphne DeLeon and Natalie Murphy

In the late twentieth century, a series of desegregation laws within the Philadelphia school district were passed and failed due to political and societal pressures. They were often met with resistance from parents and community members who opposed and feared racial integration, oftentimes rooted in ideology surrounding reverse racism. In response to the poor implementation of racial integration measures, Philadelphia student groups organized protests against segregation and the mistreatment of Black students and teachers.

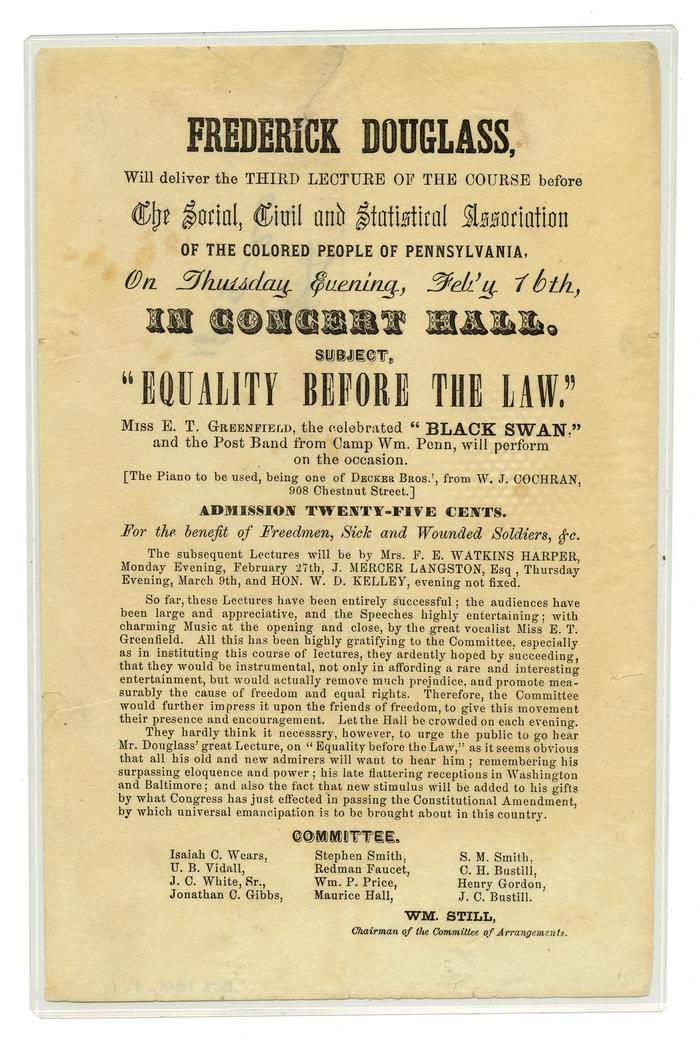

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s inspired the action of several student-led groups in the greater Philadelphia area. Students from various backgrounds, communities, and cultures organized a series of protests and newsletters that demanded racial equality and integration within the curriculum and culture, such as the Groovers. The Groovers were unique in the fact that it was largely composed of Black high schoolers and youth; however, they were also assisted by many big-name Black organizers, including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Some of their most prominent work was reflected in their late 1960s newsletter, named The Black Ghetto. Within this series of written works, Black teenagers authored several different columns, including a multitude of perspectives and experiences they faced in a predominantly white country. In the left-hand corner of the newsletter is a large Black power symbol, followed by a brief explanation of The Groovers’ mission. Their mission states they want to educate and bring “North, South and West Philly closer together” (The Black Ghetto).

The January 1970 issue of The Black Ghetto published an article titled “I Believe,” which focuses on the perspective of a Black youth who shares their deep dedication to the movement for racial equality. The author demonstrates a rare zeal, a treasure to historians and the public alike, emphasizing the systemic injustice against Black people and utilizing phrases such as “being Black has taught me deep down in my bones that I must risk everything to destroy this system” (The Black Ghetto, Thelma McDaniel Collection #3063, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1). “I Believe” and the overall publication of The Black Ghetto reveal the revolutionary influence of a powerful grassroots movement within the larger push for racial equality. An incredible community of Black youth, who used written and physical advocacy to challenge an inhumane system, ultimately led to the passing of anti-segregation measures in Philadelphia.

Despite the student protests against unfair treatment of Black students, by the early 1970s, the vast majority of Philadelphia public schools remained legally classified as segregated. In a complaint filed against the School District of Philadelphia by the Pennsylvania Human Rights Commission, the organization responsible for enforcing civil rights laws in Pennsylvania, the commission found that the School District had failed to follow through on its proposed plan to desegregate Philadelphia public schools. In fact, the number of segregated schools had increased from years prior; around 49% of Philadelphia public schools were over 95% one race at this time, a 7% increase from just a few years prior, and over half of Black students in Philadelphia attended a school that was over 95% Black. Even programs that were meant to encourage desegregation failed to be integrated; 8 out of the 10 magnet schools in the district were still legally segregated at the time of the complaint.

Many of the special and after school programs introduced by both the school district and by outside institutions that were meant to encourage desegregation were actually used more as legal loopholes by the school district to make it appear as if schools were less segregated than they were. Many consisted of students of different races working together in isolated classes/programs before returning to their largely segregated schools. The sad reality is that despite the efforts of Black students and teachers, the school district remained far behind in terms of fulfilling its desegregation promises. Even with Richardson Dilworth, who was known for supporting civil rights and reforms, as the head of the board of education, the school district was still extremely lacking in implementing its desegregation plans.

During the first week of Summer Academy, our group visited City Hall to observe the inner workings of Philadelphian politics. Black Philadelphians have only had representation in politics in recent years. Despite having always made up a large percentage of the population, Black Philadelphians were largely excluded from public service until 50-60 years ago; only a few portraits of Black mayors were exhibited. The largest feature of Black people within City Hall was a short hallway on the fourth floor, in which a small collection of artwork created by Black artists was seen. The exhibit had little to no accessibility, with little connection to Black involvement in politics. Now more than ever, it is necessary to maximize the public’s accessibility to exhibits created by people of color.

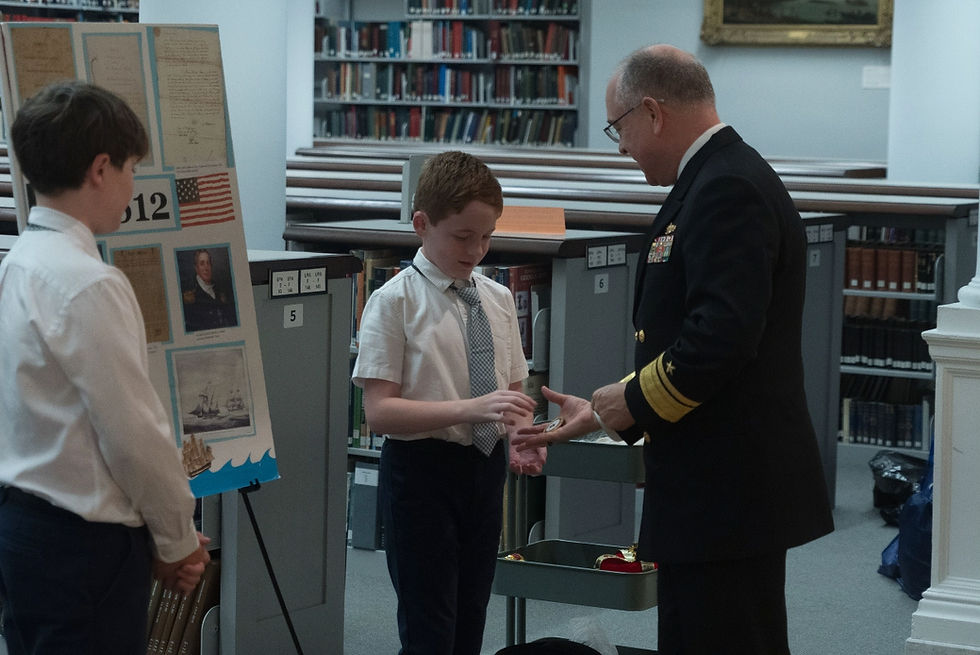

Daphne DeLeon is a senior history major at Temple University. Natalie Murphy is a junior history major at Villanova University. DeLeon and Murphy were participants in the 2025 Public History Summer Academy for undergraduates. Students spent a week in August learning about archival research and public history practice and careers. Drawing on the vast collections at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the students focused their research on citizen action and education in Philadelphia. Visit https://www.portal.hsp.org/phisa for more information.

Comments