Celebrating Disability Pride in the Archive

- sbemak

- Jul 30, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 13, 2025

By Rhianna Searle, Haverford College '27

Programs and Communications Intern

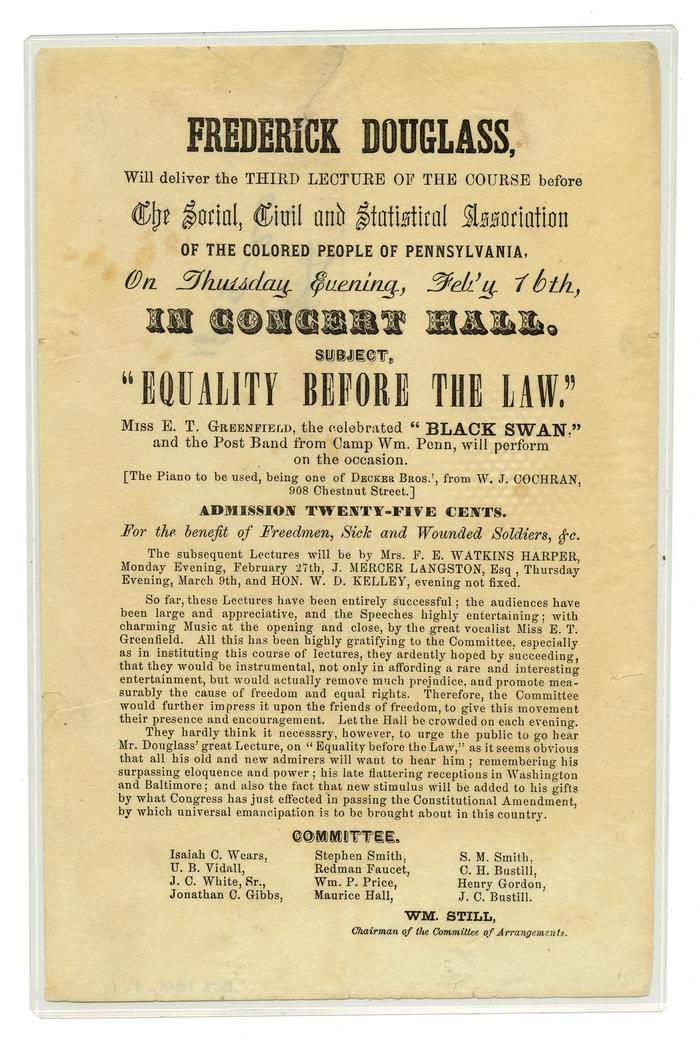

The disabled community is as diverse as it is vibrant. Comprised not just of people with physical impairments, but those with invisible disabilities, neurodivergence, mental illness, and sensory differences, “disability” is a term that can encompass cerebral palsy to dyslexia, blindness to autism, and is an identity of pride for many individuals. The history of disability in the United States is often dark—shaped by eugenics, inhumane institutions, and lack of accessibility paired with stigma that barred disabled individuals from full participation in society. However, July celebrates Disability Pride Month, recognizing how far we have come in the fight for disability civil rights. It occurs in July to commemorate the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act on July 26, 1990. In honor of Disability Pride Month, I took to the archives in search of disabled joy and innovation.

As an anthropology student at Haverford College, and someone who identifies as disabled, I believe it’s important to bear witness to the hard history but also to recognize the people who created community, fought for their rights, and lived vibrant lives. Disabled people can be incredibly innovative—navigating a world not designed to meet their needs. I believe the disabled community has much to teach us about centering joy and full humanity in a world that narrowly defines who is of value.

Doing historical research on marginalized communities presents a unique set of challenges. As with many other oppressed groups, much of the archival record tells the story of disabled people from an outside perspective. HSP, for example, has a collection of Philadelphia’s almshouse records, a valuable resource for disability studies and genealogy, but one in which we must search for disabled voices between the lines. Another challenge I faced was the evolution of language. I had to use outdated terminology such as “crippled” and “insane” as search terms. While painful, these are some of the techniques required when digging for marginalized stories. However, the voices are there if you look for them.

Some of the items I discovered in HSP’s collection include prints by artist Albert Newsam (1809-1864), a famous deaf painter from Philadelphia, the Widener Memorial School photographs (1950s and 60s), the Overbrook School for the Blind yearbooks (1970s), and the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf photos (1930s). These highlight the creativity and joyful experiences of people in the disabled community.

I discovered a 1978 newspaper article written by Dr. Frank Bowe, Director of the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD), about the annual ACCD Delegate Council meeting in Washington D.C. People from around the country came there to organize for their rights, a gathering that Bowe emphasized as uniquely situated in the American democratic tradition. Participants met with congressmen to fight for public transportation access and the enforcement of Section 504 regulations. They also engaged in advocacy training, some of which was facilitated by Philadelphia’s own Public Interest Law Center. Bowe talks about cross-disability solidarity, the collaboration between people with different types of disabilities, a value that would become one of the 10 Principles of Disability Justice years later.

Cross-disability solidarity can be found in other spots in HSP’s archive, such as the Shut-In Society photographs from the 1940s, which depict blind employees creating wheelchairs and other mobility aids—providing employment as well as fulfilling community need.

I also found a “Deaf person's guide to Philadelphia, past and present” (1979) created by the members of the Philly deaf community in collaboration with the Free Library of Philadelphia’s Office of Deaf Services and the Community College of Philadelphia’s Continuing Education for the Deaf Advisory Board. It describes the accessible options at museums and other places throughout the city, highlights deaf community organizations and history, and features fun art by a deaf artist on the front cover. Created more than a decade before the ADA, guides like these are inspiring examples of the disability community taking care of itself. HSP also has a 1976 map of Philadelphia’s Historic District with a braille overlay—yet another example of ways people worked to make our city accessible before legislation mandated it so.

In many instances, disabled people were supported by able-bodied people, and while those efforts are valuable, it’s important to highlight the disabled community supporting itself. Pennsylvania Home Teaching Society for the Blind, founded in 1882, “show[s] the workings of a society that was founded by a blind individual, employed primarily by blind teachers, and focused on educating blind adults”. The Home Teaching Society used the Moon alphabet, which was developed by Dr. William Moon, who himself was blind.

One of my most interesting finds was a book of poetry and short essays entitled Musings of a Blind and Partially Deaf Girl by Mary Ann Moore. Published in Philadelphia in 1873, this book provides an interesting opportunity for analysis of disability culture in a different era. The opening poem, “The Authoress’s Petition”, was particularly interesting to me in the way it acknowledges the idea of disabled people as lower-class citizens yet also asserts Moore's authority and desire for self-sufficiency. She recognizes publishing this book of poems not simply as a piece of art, but as a tool for her independence and financial security. But it’s “not self alone” that she wishes to support—she hopes her words might provide comfort to others who experience hardship. A later piece in the book reveals that Moore is actually in her late 40s, not a girl at all, but a woman. The choice to advertise herself as a “girl” may shed light on the infantilization of people with disabilities, but also how Moore understands her societal place and chooses to use that to her advantage to draw people to her work. Throughout the collection, deeply grounded in her Christian faith, she navigates the line between common ideas of the time, such as disability being a result of sin, and her belief that disabled people still have much to offer society.

Doing this research was a meaningful experience for me, allowing me to apply what I learned in my college course on Disability Studies to primary source materials. On a personal level, it allowed me to see myself reflected in the archive, feeling a sense of kinship with the fellow girls with orthotics and ankle braces across time. This project truly lived out HSP’s goal of “making history yours.”

If you’re curious to dig deeper into disability history, HSP’s publication Legacies, did a Disability Histories of Pennsylvania edition a few years back. This was a valuable resource for me when I was doing my research, and you can read all of the articles online.

Moloshok, Rachel, “Teaching ‘the talent of blindness.’” Pennsylvania Legacies, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 2017, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 3-5.

Comments